Welcome to a new Sitcom Tuesday and the start of our coverage on the best of Friends (1994-2004, NBC), one of the most popular American television comedies of the past 30 years. The entire series has been released on DVD, Blu-ray, and is streamable on several online platforms. [For these posts, I studied the uncut episodes as they appeared on the original DVDs.]

Friends stars JENNIFER ANISTON as Rachel Green, COURTENEY COX as Monica Geller, LISA KUDROW as Phoebe Buffay, MATT LeBLANC as Joey Tribbiani, MATTHEW PERRY as Chandler Bing, and DAVID SCHWIMMER as Ross Geller.

The prospect of finally covering Friends is a daunting one — not just because there are 236 episodes to survey, but also because it remains one of the most popular American sitcoms ever produced. Turn your TV on right now and you can probably find it playing somewhere on cable. In fact, there are people reading this essay who watch nothing but Friends and whose obsession for it will never waver…Frankly, I worry when shows that inspire such fanaticism (like Seinfeld and The Golden Girls) come up here, for the cult surrounding a specific work is something that shouldn’t infiltrate our quest for quality. That is, I consider myself a Friends fan — I got the first season on DVD the year it was released — but this is tempered by a broader truth: I’m a fan of American television comedies. Meaning, my love of Friends is part of my love of the Sitcom (writ large), and it’s within this wider appreciation that I approach every series we cover. So, to those who are exclusively Friends fans, if you’re seeking reviews that regard the show above the rest of the medium, you will be disappointed. Nevertheless, I hope you’ll still find my analysis, in search of the series’ best moments, fair, because I enjoy the show and these characters, too. And I note all this now to let everyone reading know that these subjective commentaries won’t be coming from either of the extreme emotional poles around which most discourse surrounding the series spins — you know, where Friends is called either the BEST SHOW EVER or the WORST SHOW EVER. I’m in neither of those orbits, but I understand them both, for as with everything popular, a countering criticism is also popular…

… for reasons valid (it’s healthy to be skeptical about highly visible works — maybe you take issue with the series’ crass commercialism or the broadening of its characterizations — I get it; I’ll have a lot to say on these matters, too), invalid (having nothing to do with the show or its quality, but rather, the way to which others respond to the show, like NBC, which sought to replicate its success with aesthetic companions that were indeed inferior), or irrelevant (like having a personal distaste for the low-concept “Singles In The City” mold, or rejecting, on principle, its well-established tonal conceits — discussed below — which the show can’t actually be considered a failure for reinforcing as intended). Okay? So, I know where you’re all “coming from” and I know the ways in which Friends, by designing itself for a mass appeal, inevitably alienates those who dissent by choice or by accident… Now, let’s set aside what people think about the show, until the moments when critical and commercial reception play a part in informing what’s on-screen (and trust: it will; stay tuned…), and instead focus on Friends‘ genuine merit, based primarily on standards that the show establishes. That’s the purpose of my coverage. (Also, I feel it essential to say that, like every series here, I view Friends as a period piece. It was produced and intended for prime consumption from 1994 to 2004. It no more influenced its times as it was influenced by them. Thus, the popular trend of revisiting a past work and forming commentary only around how it upholds the viewer’s own contemporary mores is something that can’t be used to determine what works and what doesn’t. Expecting a reflection of today in a work not produced for it guarantees disappointment. Therefore, while seeking the finest episodic samples, I’m looking at Friends as a product of its era.)

With those terms set, I can introduce a recurring framework for these commentaries: the idea that Friends isn’t just a situation comedy, but more specifically, a romantic comedy. Yes, Friends is a rom-com, and that’s a good part of why it’s so broadly popular with some and so naturally loathed by others. We touched upon this notion briefly in coverage of Mad About You. Here’s an excerpt of what I wrote two months ago, in relation to that series: “. . . the undercurrents of romance and optimism are forever prevalent . . . [but] Mad About You’s overarching sentimentality really cries out for a counterbalancing comedic punch (something Friends was generally good about maintaining as part of its thesis — the other side of its emotionally forthcoming accessibility), for AWWWW is not the same as HAHAHA, especially in a genre that, by definition, demands the latter.” Before we talk about Friends’ humor, I want to address this suggested romanticism. Fundamentally, Friends is emotionally forward, tonally optimistic, and basically grander-than-life. Unlike Seinfeld, which shares a similarly low-concept “Singles In The City” premise, Friends actually has a positive view of humanity, of love, of life. It’s not cynical. No, in fact, it’s feel-good, rose-tinted, and aspirational. We see ourselves in the Seinfeld characters, and our ideal selves in these six joyful, beautiful, communal Friends, all of whom also have a happy, goodness-affirming world surrounding them, where frequent laughter, the regular expression of feelings, and meaningful human interaction are held up as essential tenets of modern life. This positivity — showing people what they want to see and affirming its value — is why, I think, the show was and still is such a success. So, when the series most embraces this elemental style — with an emphasis on the relationships and core friendships — it most feels connected to a greater thematic purpose… the series’ thesis (if you will), which is reflected through specific romantic constructs, like Ross/Rachel.

This romance, an aesthetic imparted by creators David Crane and Marta Kauffman (who previously showed their romantic comedy chops on Dream On, covered here last year), grants the series license to employ more than a “typical” sitcom’s allocation of narrative contrivances, for they come in tandem with this rom-com sensibility, where emotional exaggeration — for the right reasons — is encouraged. And because this is part of the series’ thesis, we make allowances for beats that on other sitcoms — lesser sitcoms — would not be permissible. I’m referring now to the show’s sometimes dangerous use of story, particularly lofty arcs, which always exist under some pretension of being a noble tool for character exploration and progression (even if the results don’t bear out as such and are in fact harmful to the characterizations) and the network TV business of ratings-led gimmicks and cliffhangers. As we’ll see in weeks ahead, Friends’ penchant for saving its big dramatic moments for Sweeps and building each year to a requisite overblown season-ender (what we’ll sometimes refer to as its “commercialism” — for this is about money, not quality) isn’t always great for laughs or character. This is a legitimate complaint, for, as regular readers know, there is nothing more important in a situation comedy than character, and just because Friends is a rom-com, that doesn’t mean its regulars should take a backseat to story concerns, regardless of how tonally appropriate. No, character is the only thing that makes any of this worthwhile, for we have to keep enough faith in each regular’s emotional truth to invest in their relationships (on the macro level) and in their weekly narrative motivations (on the micro level). Thematically, we’re not expecting 100% fidelity to realism (to which Seinfeld unwisely professed allegiance) — just a brand of honesty congruous with the show and these players. Humanity, not reality.

Meanwhile, the decision to offer an average of three plots per episode — a formula that becomes more obvious in Season Two than One — is also a characteristic of Friends with which we have to contend. (And one can look here and at Seinfeld for being the most aggressive promulgators of a template that now seems commonplace today — for better and worse.) By definition, though, this design leads to uneven episodes — making lists of this nature difficult to craft… Interestingly, we’ve seen this style before on shows like Seinfeld, but unlike its MSTV neighbor, Friends doesn’t feel as much pressure to narratively unite each thread, and it isn’t as enamored of the concept of “dovetailing.” This is a mixed blessing: heady structure doesn’t become a regular obstacle to the honest presentation of character, yet the more connected an entry’s stories are — either by theme, location, or narrative — the easier it is to enjoy them all; so, disconnection isn’t worth celebrating either… Actually, what threatens the depiction of character most is either the story ideas themselves (they’re either plot for plot’s sake, not born from character, or worse, destructive to their principals’ emotional truths) or the accompanying, ever-present, and valiant pursuit of laughs. Hold that thought, for speaking of laughs, the other reason I think Friends is so successful, aside from the romance, is the other half of its “rom-com” label: the comedy. Simply put, Friends is funny, and I think its detractors lessen their arguments when they don’t concede that the show is always pushing its humor to the fore, and more often than not, succeeding. Sure, it’s got a lot of touchy-feely-ness (from its tone), and wants to ensure that all of its relationships are doused in a form of forced sincerity (that we each either accept or refuse), but while it’s going to wear its “heart” on its sleeve, it’s also going to tickle our funny bone — using humor to cut anything seemingly heavy.

This comedy helps frame all the series’ thesis-rooted moments of earned emotional forwardness, while also deflating their sometimes aggrandized self-importance (especially during times in which these moments may be unearned, and the story interests, regardless of unreliably professed intent, seem big and character-subjugating). In this way, the humor is equally important as the heart… And, I have to tell you, there’s nothing I respect more about Friends than its perfectionist stance with regard to laughs. Notorious in the industry for its long production nights, the Friends crew was always trying to punch up a script and make it the best and funniest it could possibly be — rewriting between takes in response to the feedback gleaned from the studio audience, which was allowed to serve as a material barometer. (That’s how a show gets a good product!) However, just as “heart,” through story/arcs that intend to embody it, can get in the way of the comedic depiction of palpably human characters, comedy can also be a villainous force. For as we will see over the course of the series’ run, when the storytelling becomes bolder and more episodically all-consuming, the laughs heighten as well. This results in a lot of broadening for these characters – sometimes for laughs that are indeed worth this larger posturing, but also sometimes at a price: a strain in our ability to maintain faith in the type of honesty needed to support these inflated romantic stakes. Luckily, in this era, the biggest concern is defining the characters and having them motivate episodic stories, and while the inherent structure propels unevenness, narrative value is less important than a tonally congruous depiction of the players (and than the laughs in accompaniment — demanded by genre). Also, character, however concerning situationally (micro), will remain consistent enough throughout the run to hold onto the audience’s investment — even when the regulars’ growths (and their relationships) are halted, ignored, or regressed for the sake of prolonging the endgame.

Now, let’s talk about the Friends. Generally, I think they, too, are fairly consistent — and the fact that each one of them appears in all 236 episodes is impressive. On basic terms, everyone is well-defined and no performer can reliably be deemed a weak link — even though, in both character and cast, some begin more developed than others. In terms of character, the best drawn in the pilot are Ross, Rachel, and, by virtue of Perry’s own distinct voice, Chandler. (The extent of Chandler’s definition on the page is obscured by Perry’s unique intonations.) Meanwhile, despite a grounded sense of authority that would suggest a characterization, Monica serves a mostly functional purpose – she’s the anchor, the reason this group is connected, and, through Cox’s casting, the most accessible point of entry for the audience. But she lacks a certain definition (perhaps because the original conception for her character — an embittered Janeane Garofalo type — was dropped). Yes, she does play the straight woman, and gets a story that helps define the series’ own Gen X form of liberality with regard to sex. Yet the reason for her narrative existence is simple: to provide a contrast with Rachel. Thus, Monica exists in relation to Rachel, and without a strong, comedic voice of her own. The characters with even less definition at the start, though, are Joey and Phoebe. Kauffman and Crane will admit to a lightly penciled version of Joey in the pilot, citing him as not different enough from Chandler, but Phoebe is also thin in everything except a single monologue, from which Kudrow extrapolates a lot, first hinting at the great comedy this actress will bring to the role. Fortunately, the strength of her performance fuels a comedic honesty that fleshes out what’s quiet on the page – a daffy New Age chick whose dark circumstances contrast comedically against her seemingly sunny disposition – giving her definition that, for the most part, is locked and loaded within the first season. (And this will remain the case for a while, until she takes a turn…)

With Joey, the show quickly sees what LeBlanc is doing and magnifies it: Joey becomes a little denser, in tandem with his established persona as a struggling actor, while his womanizing (suggested in the pilot) is expanded upon and then played as oppositional to Chandler’s. Thanks to these efforts, by Season Two, Joey has a firm characterization, and his friendship with Chandler then becomes one of the series’ emotional bedrocks. However, his characterization will change a lot, too – undergoing a broadening that really corrupts the humanity that he and all the other regulars exhibit during the show’s best years… As for the actors, I think, again, they’re collectively strong and individually impressive — improving tremendously in skill with each year. But from the beginning, the standouts, in my view, are Schwimmer and Kudrow. They are the two, above all else, who seem to find character moments that wouldn’t be textually obvious. To some extent, all six of the Friends will be able to do this before long, although characterization problems, for some, will complicate this fact… Regarding the text itself, the show is certainly an ensemble. (Kauffman and Crane consciously avoided doing another one-lead show, like Dream On.) But there are focal points. Naturally, Ross and Rachel are, from the start, the show’s narrative and romantic engine. Kauffman and Crane like to suggest that Ross/Rachel was something they felt their way through during the first season (after an initial pitch that focused on Monica and Joey), but the pilot is clearly structured — and perhaps director Jim Burrows deserves credit for finessing this matter — to make the audience invest in this coupling as a centripetal concern. It’s there from the jump; he is kicked out of a bad relationship and she runs from one, setting up two of the three main arcs: Rachel‘s development from girl to woman, and Ross’ pursuit of Rachel. They drive the series here.

The third main arc is Monica’s search for romantic fulfillment, and while she’s starved of her own comedic propellant at first (unlike the others — even the hazily constructed Joey), she is the anchor of the entire ensemble, and her relationship with Rachel, next to Rachel’s with Ross, is the pilot’s most seminal. These three spend most of the first season — and heck, most of the second — on a higher tier in story. Accordingly, among Season One’s primary tasks is finding ways to better define Monica. Much of what sticks is established in the first installment following the pilot — she’s neurotic and obsessive when it comes to cleanliness and order, her parents’ preference for Ross has instilled in her a sense of competition, and there was a time when she used to be overweight. That’s actually a lot of great stuff. Putting it into practice is harder, though, and the season carefully explores these themes — mostly her obsessive compulsiveness — before it casually finds, eventually, a balance in her characterization that may not be great for story, but offers her enough laughs, fits her in well with the others, and persists throughout the next few years (until the show pairs her with Chandler, curing her story problems, but highlighting her comedic issues through an unfortunate broadening)… So, although this is a series that needs all six of its regulars to function, the narrative intentions in this early period center around Rachel, who enters their world and is built for growth, Ross, who has a clear rom-com objective (winning Rachel), and Monica, who is the glue. And even though characters like Joey, Chandler, and Phoebe may be funnier than the three drivers in these early years, the show feels like it’s working best when it caters to the players in the pilot who were positioned more prominently. There will be tension ahead as the series tries to negotiate an elevated ensemble, a diminished Ross/Rachel, and a set-up that demands a central couple…

As for the first season, there are three big stories the year tracks beyond its episodic interests: the pending birth of Ross‘ child (which is set up in the second entry and includes recurring help from Carol and Susan — Ross’ ex-wife and her new partner), Rachel‘s growing independence (she takes a job as a waitress and has her first really steamy affair with an Italian hunk), and Ross’ attempts to ask out Rachel – the most obviously rom-com part of the season, and the one that I most believe accounts for its popularity, its success, and in this era, its best episodes. (Allegedly, it was Burrows who insisted the year structure itself around the latter — with the finale not being about Ben’s birth, but the latest chapter in Ross/Rachel.) All three of these interconnecting arcs work because they’re directly correlated to the emotional hooks provided to us in the pilot. They’re part of the series’ premise — its thesis — and reaffirm that optimistic, rom-com view of the world. (Even Marcel the Monkey can be seen as a character-rooted manifestation of Ross’ loneliness as a result of circumstances established in the pilot, and he’s a tool that the show uses to help Ross work through his fears of becoming a father. Personally, though, I think the monkey is also a gimmick — an unnecessary one — and he cheapens the episodes in which he appears.) While these early storylines (themselves low-concept in comparison to what’s ahead) are a healthy outgrowth of character as we know ’em, future endeavors may not be able to claim the same. I’m going to save discussion on how the series’ commercial concerns affected its creative ones for next week. But here, I think some history is helpful in setting up how the show first justifies being designed for a broad, young audience.

We’ve already talked about how Friends used self-affirming aspirational optimism to drive its appeal, but I also want to point out that the premise — the “Singles In The City” that turned into a phenomenon by virtue of NBC’s attempts to maintain this younger-skewing audience for additional comedies that could debut on Must See TV Thursday and then become anchors on other nights — is not original; other shows had employed similarly low-concept targeted demo constructs. (Heck, FOX that season had familiar titles in Living Single and Wild Oats.) What made Friends fresh and worthy of replication, however, were the characters and the show’s ability to derive comedy from their depictions, all the while creating audience investment in their respective growths. In explaining why Friends was such a quick hit — by episode ten, it was already beating its well-established and critically acclaimed lead-in, Mad About You, in total viewers (which is part of what inspired NBC to move the series to a post-Seinfeld slot during February Sweeps, so its audience could grow before it would supplant Mad at 8:00) — I think one has to go beyond these notions of self-identification and ego-driven positivity to note the quality of what was being produced. (See these lists.) And at the time, the Television Academy also recognized the year with nine Emmy nominations (including for series, writing, directing, and acting — Kudrow and Schwimmer) — the highest annual number until Season Eight (following several backlashes and a seeming “comeback”). I think they got it right here — this is a great debut season of a series that is surprisingly consistent (despite inner episodic fluctuations), and it already appears destined for much improvement. But can it prove to be as well-written as it is popular? That’s for next week… In the meantime, I have picked ten episodes that I think exemplify the season’s strongest. (They are listed in AIRING ORDER.)

Regular writers this year include: Marta Kauffman (Dream On, The Powers That Be, Grace And Frankie) & David Crane (Dream On, The Powers That Be, Episodes), Jeff Greenstein (Dream On, Will & Grace, Desperate Housewives) & Jeff Strauss (Dream On, All Of Us, Shake It Up), Alexa Junge (Veronica’s Closet, The West Wing, Grace And Frankie), Adam Chase (Veronica’s Closet, The Weber Show, Better With You) & Ira Ungerleider (Jesse, How I Met Your Mother, Angie Tribeca), and Jeffrey Astrof (The Wild Thornberrys, The New Adventures Of Old Christine, Trial & Error) & Mike Sikowitz (The Wild Thornberrys, Grounded For Life, Rules Of Engagement).

01) Episode 1: “The Pilot” [a.k.a. “The One Where Monica Gets A Roommate”] (Aired: 09/22/94)

Rachel runs out on her wedding; Monica has sex on a first date; Ross mourns his break-up.

Written by David Crane & Marta Kauffman | Directed by James Burrows

Although I never think of Friends‘ pilot when I consider the Sitcom’s best — due to how much the characterizations changed over the course of the show’s run; heck, over the course of the season’s run — this opening installment is, nevertheless, an honest establishment of the arcs that will take center stage through, at least, the first two years of the series. Rachel leaving her fiancé and having to make it on her own in New York is the catalyst for the action, and her development will be a focal point. Meanwhile, Ross’ interest in Rachel is set up to be the primary engine for the audience’s emotional investment, and Monica is billed as both the anchor and a relatable character whose own quest for love, contrasted against Rachel’s, is to be another through-line. Indeed, these three regulars are given an elevated prominence within the episode (and the season), but everyone has a certain amount of humanity. Some are funnier than others, and some are better defined than others (see above), yet this already looks to be a strong ensemble. As for how the outing compares to the rest on this list, it’s not the funniest — test audiences indicated that to NBC — but because this is a series predicated on growth (at least, for a while), this is a must-see, as all the room for development is fascinating.

02) Episode 5: “The One With The East German Laundry Detergent” (Aired: 10/20/94)

Ross and Rachel do laundry; Phoebe and Chandler dump their dates; Joey doubles with Monica.

Written by Jeff Greenstein & Jeff Strauss | Directed by Pamela Fryman

Season One contains a lot of “firsts” and this excursion is, among other things, the first time that a script divides its six leads evenly into three groups of two, which is going to be one of the most common structures in years ahead. The weakest link here is the plot for Monica and Joey, the two characters whose sources of comedy still have the furthest to go in terms of development. But it’s an adult story and the pairing’s novelty secures intrigue. The emotional core, no surprise, is Ross/Rachel. This week, the pair does laundry together: the first time they’re alone in an individual narrative, and the first time we get some validation that the arc established in the pilot — not only is it still on the show’s mind, but it’s also worthy of investment, given the chemistry of the performers and the characters. The most memorable plot, though, goes to Phoebe and Chandler, who each decide to dump their respective partners at the same time and place. This is a pairing of, up to now, the two funniest regulars, and the contrast of each attempted break-up is a great indication of their burgeoning personas. And, of course, it provides our first taste of Janice (Maggie Wheeler), a classic recurring character who will broaden within her next two turns, but always represents the show’s commitment to comedy.

03) Episode 7: “The One With The Blackout” (Aired: 11/03/94)

During a blackout, Ross attempts to ask out Rachel, and Chandler is stuck with a model.

Written by Jeffrey Astrof & Mike Sikowitz | Directed by James Burrows

One of several candidates for MVE (Most Valuable Episode, a single-episode designation that I give out for every season covered here), this installment was part of a night-long Sweeps stunt where three of the four shows in NBC’s comedy block — Mad About You, Friends, and Madman Of The People (all of which have been covered) — dealt with a citywide blackout. (Seinfeld at 9:00 refused to engage in the gimmick.) The value of this offering to Friends, specifically, is three-fold. One, it’s designed so that almost all of the Friends are at the same place at the same time, which is what we already most want to see — six people (or five), for whom we are starting to care, bouncing off each other. Two, Matthew Perry’s Chandler gets to carry an entire comedic subplot on his shoulders when, in the first stunt casting of the series, he’s stuck in an ATM vestibule with model Jill Goodacre. And three, it furthers the Ross/Rachel arc when Ross tries to ask her out and is stymied first by a manic cat — in one of the best sight gags from all ten years — and then by a Paolo. Now, personally, I think Paolo is a necessary speed bump to delay Ross’ arc, but he never really pays off on his own. And while I like the progression of this semi-serialized storyline, there are funnier outings below that make better use of stronger, more developed characterizations. So, this is good, but it’s still green (even for Season One).

04) Episode 9: “The One Where Underdog Gets Away” (11/17/94)

Monica hosts her first Thanksgiving for a group of people who don’t want to be there.

Written by Jeff Greenstein & Jeff Strauss | Directed by James Burrows

Credited to two writers who had worked with Kauffman and Crane on Dream On (see more), this Emmy-nominated script is notable for introducing what would become a Friends staple: the annual Thanksgiving feast. It’s a show that’s mirrored later — Ross singing The Monkees to Carol’s stomach feels like it’s called back subliminally when he sings Sir-Mix-A-Lot to Emma in Season Nine, and of course, the “Thanksgiving that doesn’t happen” is heavily paralleled, but with an intentional lock-out, in the final entry from this holiday catalogue. Yet what makes this installment meritorious on its own is that, once again, it puts all the Friends together for what promises to be a unity of time, place, and action, which aside from being something that I personally believe the multi-cam format thrives when offering, also generates the most revelatory moments for these characters. Here, the show quietly builds backstories for second tier regulars like Phoebe, Chandler, and Joey, while also finding a way that Monica can be funny — as the control freak pushed to her limits. Now, we don’t really get all the regulars together at once as much as we will in the other Thanksgivings, but this reveals the template’s potential.

05) Episode 13: “The One With The Boobies” (Aired: 01/19/95)

Chandler sees Rachel naked; Joey learns a secret about his dad; Phoebe dates a shrink.

Written by Alexa Junge | Directed by Alan Myerson

A mixed bag, this one! The A-story with Chandler accidentally seeing Rachel naked, thus setting off a chain of events in which she tries to see him naked, but ends up seeing Joey, and Joey tries to see Rachel naked but ends up seeing Monica, and Monica tries to see Joey naked but ends up seeing Joey’s father is… juvenile (in its blatant attempt at titillation) and unoriginal (we’ve seen this same idea used before on Must See TV Thursday in Seinfeld). But it doesn’t not make sense for these characters, and because the sexualization of Rachel is part of the Ross/Rachel arc, it doesn’t necessarily feel out-of-place either. What does feel slightly out-of-place is the story with Joey, where he learns his father (Robert Costanzo) has a mistress (Lee Garlington) about whom his mom (Brenda Vaccaro) already knows. This is obviously the mid-Season One episodic attempt to deepen Joey — we saw it with Chandler and his mom (and with Phoebe and David) — and it is basically successful, even though it asks a little much of the audience. (It’s too many new characters in which to invest, when our only concern should be Joey.) However, it’s the C-story that truly makes the offering worthwhile, as Phoebe dates a shrink (Fisher Stevens) who analyzes her friends so brilliantly, astutely, hilariously — with a Seinfeld-ian self-awareness that’s foreign on this series and indicates how tonally disparate these two oft-compared hits are.

06) Episode 14: “The One With The Candy Hearts” (Aired: 02/09/95)

Ross has a date on Valentine’s Day; Chandler reunites with Janice; the girls perform a ritual.

Written by Bill Lawrence | Directed by James Burrows

Valentine’s Day wouldn’t become an annual tradition like Thanksgiving, but it’s easy to see how it could have been, for the holiday plays directly into the series’ rom-com aesthetic, granting the show license to indulge in the emotionality it holds dear. This script, credited to non-staffer Bill Lawrence (creator of Spin City, Scrubs, and Cougar Town) has three Victories in Premise, and doesn’t let them down. The least notable is the girls’ fire hazardous anti-Valentine’s Day coven, which starts great but contrives for a comedic crescendo. The romantic nucleus, meanwhile, (as usual) is Ross, who goes out on his first date since the divorce and is surprised to see Carol and Susan. It’s not a hilarious subplot, but it reminds the audience of the seasonal arc implanted in the first episode following the pilot (the impending birth of Ross’ baby) and it gives Carol/Ross a fairly long one-on-one scene that is needed for our further investment in the story. But, for the third time this year, the real comedy comes from a Chandler-Janice subplot, when Joey and his girlfriend unknowingly pair the two on a blind date, and they temporarily get back together — much to Chandler’s chagrin. The bed reveal is hysterical, as is the bit where the others catch her in the hallway; yet it’s the scene between them in the coffee house that truly cements her as a Friends icon. (If only she could stay exactly this broad — no broader!)

07) Episode 17: “The One With Two Parts (II)” (Aired: 02/23/95)

Rachel and Monica swap identities while dating doctors; Phoebe worries about Joey and Ursula.

Written by Marta Kauffman & David Crane | Directed by Michael Lembeck

Whenever I have occasion to discuss a two-parter, unless both parts are so darn good (or the rest of the season is otherwise lacking), I typically only choose one half — because, in my experience, two-parters often have trouble with story (either it’s too much, and there’s no time for character, or too little, and the pacing of the comedy is wrecked), and, also, I basically get to discuss two “for the price of one.” Here, Part II is better than Part I, but they’re both important entries that do serve a combined purpose: transitioning the series to its new post-Seinfeld slot at 9:30. Coming during February Sweeps, Part I aired at 8:30, right after Mad About You, and concerned itself with explaining the Ursula-Phoebe connection (while featuring a corresponding walk-on from Mad‘s Helen Hunt and Leila Kenzle). Part II then aired at 9:30 after Seinfeld, and boasted guest appearances from George Clooney and Noah Wyle, of 10:00’s ER, as a pair of unrelated doctors. These cameos were felt necessary to help build Friends‘ audience, for now it was being groomed to become not just an anchor in the fall, but a Thursday night anchor in the fall — a most prestigious honor. Given these intentions, there’s a sense of gimmickry in both halves, and while Part II feels more egregious — because of Clooney/Wyle — it’s also the bolder, with more laughs (Aniston and Cox are having fun) and more heart (the Joey/Phoebe scene is beneficial for both). And because this is a great representation of the series’ network-based commercialism, I think it’s too honest a look at Friends to not highlight.

08) Episode 18: “The One With All The Poker” (Aired: 03/02/95)

The men and women face off against each other in poker.

Written by Jeffrey Astrof & Mike Sikowitz | Directed by James Burrows

My choice for the Most Valuable Episode (MVE), this installment was actually written and produced earlier in the year — as its 13th, a point in most full seasons where there’s a pivot. To wit, there’s a sense of movement here for two arcs established in the pilot — Rachel’s move to adulthood, represented by her financial independence, and Ross’ desire to act on his long-held feelings for her. To the first point, this offering’s subplot involves Rachel potentially getting a job in the fashion industry that would take her out of the coffee shop and progress her maturation. To the second point, the extent of Ross’ feelings for Rachel (and the deeper they go, the more we invest in both of them and their quests) are illustrated in a climactic poker showdown, the entry’s A-story, which brings all six regulars together at the same time and place, where they can bounce their generally well-formulated characterizations off one another within the confines of a poker game, a construct with which the audience is familiar — making it, for the show, an easy arena for responsive character beats. In fact, it’s here that the Geller siblings’ competitiveness, something suggested much more mildly earlier in the year, first comes to the fore in a major way, and though it will be taken to extremes later (particularly in Monica), it represents two individual victories: it further develops Monica and supplies her with another source of comedy, one which may also be able to direct the writers into crafting better stories for her, and it presents a source of conflict for Ross/Rachel directly, which is vital in their chemistry, their believability, and their ability to lead mutual stories — both when apart and, eventually, together. So, it’s the season’s smartest show. (Also, Beverly Garland guests.)

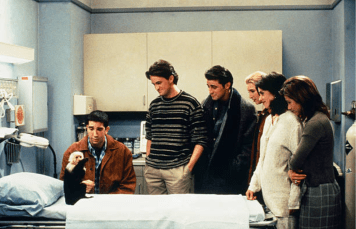

09) Episode 23: “The One With The Birth” (Aired: 05/11/95)

Carol prepares to give birth; Joey helps a single mom; Phoebe mediates for Ross and Susan.

Story by David Crane & Marta Kauffman | Teleplay by Jeff Greenstein & Jeff Strauss | Directed by James Burrows

There’s an appealing play towards the Aristotelian Unities here, as the entire outing is set within the hospital while Carol gives birth to Ross’ child. This is the arc that wasn’t established in the pilot — like the other more series-minded storylines — but set up in the following entry, thereby representing a through-line exclusive to the first year (but one that will nevertheless have consequences: an actual baby… whom we incidentally, and fortunately, won’t have to see every week). The structure of introducing this in the season’s sophomore showing and concluding it in the penultimate is genius (and something for which Burrows apparently pushed — recognizing that the pilot’s arc was built on Ross/Rachel, not Ross/Carol). But the episode itself is probably the year’s tightest, funniest, and most knowing indication of all the regular characterizations. Rachel is in her flirty element with Carol’s doctor (played by future “Single Guy” Jonathan Silverman), while Monica’s quest for a serious relationship is hammered home with an endgame plan (husband and kids) via a low-concept subplot with Chandler — which will obviously take on greater meaning soon — and Joey displays his slightly vacant brains, but abundant heart, when he cares for another pregnant woman, played by Leah Remini. Yet, what most impresses is the show’s knowledge that Ross is the center of our interest, and instead of being about Carol’s labor, this excursion reckons with his coming to terms with their dynamic — and that means Susan. It physically locks the two of them in a room together… with someone who can enhance the comedy and force a resolution: Phoebe. Top MVE contender.

10) Episode 24: “The One Where Rachel Finds Out” (Aired: 05/18/95)

Chandler spills the beans about Ross’ feelings for Rachel.

Written by Chris Brown | Directed by Kevin S. Bright

I debated about whether or not to include this installment, for just like the pilot, we’re not dealing with one of the year’s funniest or best in terms of the depiction of character. (In fact, this is one, just like the premiere, where not every regular is well-used). But it’s the crescendo of the year’s Ross/Rachel storyline, which was set up as the series’ beating heart, and there’s something both exciting as a viewer and necessary as a critic in watching the show finally — after some contrived delaying — move into a new phase of their dynamic. Just as we’ve seen on this blog before with Niles/Daphne on Frasier, another MSTV anchor, the rom-com key to kicking a tortured unrequited romance into high gear is to reverse focus and change drivers. And that’s exactly what happens here, as Rachel becomes aware of Ross’ feelings for her (from Chandler — in a great moment for him, given his history with Ross) and decides now to pursue him… even though, in the tradition of all classic romantic comedies, it’s not going to be easy for her either. As with Daphne on Frasier, when Rachel lends the perspective, it’s a breath of fresh air, and while next year may not live up to all the expectations now established, this one offering makes us privy to a thrilling climax and a very smart roadmap for what appears to be a strong Season Two. (Also, Corinne Bohrer guests as Joey’s one-episode love interest.)

Other notable episodes that merit a look include: “The One With The Dozen Lasagnas,” which is a solid progression of several arcs, as Ross learns the sex of his unborn child and Rachel ends her relationship with Paolo (after he hits on Phoebe), and more characterizations are refined when Monica’s competitiveness is used comedically as she plays on the guys’ new foosball table, “The One With The Stoned Guy,” which features a fun scene with Joey and Ross, but is memorable mostly for the guest appearance of Jon Lovitz, who definitely delivers some laughs in the situational A-story, and “The One With The Ick Factor,” which boasts a funny teleplay that’s loaded with one-liners, pairs Phoebe and Chandler for an amusing C-plot, and leads into the events of the year’s last two installments with Ross (and Ross/Rachel). Of more Honorable Mention quality is “The One With The Butt,” which gives Joey his first stab at a comedic story and also really sinks its teeth into figuring out how Monica can be as funny as her cohorts. (But it’s saddled with a try-hard Chandler plot.)

The Island of Better-Than-Their-Episode Stories: This is a feature that will debut next week. Because Friends‘ multi-narrative-per-episode template contributes to a lot of unevenness within offerings, this is a place where I will list single ideas that, had they been part of better overall installments, would have been either highlighted or mentioned above.

*** The MVE Award for the Best Episode from Season One of Friends goes to…

“The One With All The Poker”

Come back next week for Season Two! Stay tuned tomorrow for a new Wildcard Wednesday!

I’m so excited that you’re doing Friends. I do wish you had included The One with the Stoned Guy on here, but to each their own. What’s your least favorite episode of this season?

Hi, Charlie! Thanks for reading and commenting.

The lack of character-driven laughs in the A-story from “The One With The Stoned Guy” is nearly disqualifying for me, for the “climactic” sequence is built around a comedic idea for a guest star… on which (and whom) the regulars have no bearing. If that scene was geared towards the regulars instead of Lovitz (and had an actual climax), it would have been a difficult entry to not include, for the men all have fun material.

I think “The One Where The Monkey Gets Away” is the most comedically strained and narratively ill-fitting entry from Season One, so I’d cite that as my least favorite this year.

I dont like that one either though because there’s no pay-off! So he comes stoned?? So what? We don’t see what happens after. There’s no big funny crescendo. And it’s not abut Monica or Rachel. It’s about Jon Lovitz–who is funny but not well defined.

The episode I like that no one else seems to though is TOW The Butt. Joey cracks me up here! His first great episode. Glad to see it as Honorable Mention. Probably too early to be considered great overall. But it is fun.

What do you think of Barry and Mindy?

Hi, GaryK328! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I think Barry and Mindy are a means to an end — they’re used to measure Rachel’s development, and in the case of a particular Season Two episode, very effectively, too; stay tuned…

great picks , great show . love ross-rachel . can’t wait to see what u think of monica-chandler tho/.

Hi, BB! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Many thoughts on Monica/Chandler ahead — stay tuned!

Hi Jackson! I’m blown away by your smart commentary (as usual.) The rom com thing is very astute. I know many people here just click and skim the episode picks but your opening remarks are brilliant. My favorite part. always.

Looking forward to the next 9 weeks. :)

Hi, Deb! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I appreciate your kind words and am glad to know you enjoy these posts!

Thanks for covering this series. You make me think about it in a whole different way.

Curious to see what year is your favorite though. I myself am torn. I like Three and Five. (But I will stay tuned, don’t worry!!)

Hi, Elaine! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I’ll spoil now that I’m non-committal when choosing a favorite year. I think there’s a four-year stretch of excellence during which the characters continue to evolve and the laughs build… before their growths stagnate and they broaden exponentially. Stay tuned…

I agree that Schwimmer and Kudrow are the best performers. I just wish that Phoebe didn’t become so crazy and nasty as the show went broader and broader. But I’ll save that for later…

I enjoy “The One With The Stoned Guy” overall and think Lovitz is hysterical. But I agree with your decision to not include it. I don’t think I could have put it on a list ABOVE any of the ones you chose because they all have better character stuff. “Stoned Guy” is just structurally imperfect because it doesn’t do much for the women and lacks as Gary said, a big pay-off. To me, “The One With The Ick Factor” makes the best #11.

Oh, and I also hate “The One Where The Monkey Gets Away” too but I also hate that blasted ape’s first appearance, “The One With The Monkey” and think that may be my least favorite.

Hi, Nat! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Yes, “The One With The Monkey” is not a favorite of mine either — not just because of Marcel though; also because I think the episode contrives to deepen Phoebe via a one-episode relationship (with David, played by Hank Azaria) and doesn’t succeed because we don’t care about David — Phoebe’s our only concern — and aren’t given a chance to root for their dynamic. It’s a ham-fisted emotional ploy that isn’t even motivated.

His future appearances fare better, but it’s still a leap to believe the feelings that the show TELLS us they have for one another; we never got to see it for ourselves…

You know a show is great when it passes the generation test. My 16 year old daughter and her friends love Friends. We were just discussing it this past weekend. My daughter has a Friends t shirt and is getting her friend a Friends beach towel.

I enjoy all the characters but my favorites would have to be Monica and Chandler. I thought the show really hit it’s stride when these two were paired together. So looking forward to the next 9 weeks. Thanks Jackson for your always wonderful commentary.

Hi, Smitty! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Yes, FRIENDS remains one of the most popular shows ever — it’s emotionally forward, feel-good, and more importantly (for me), funny!

Stay tuned for my thoughts on Monica/Chandler and what their relationship did to the series. I’ll spoil now, I think there are positive and negative things to say…

I appear to be having difficulties leaving comments here; so, forgive me if this is appearing for the second time.

I wish I had a deeper regard for “Friends.” However, the show came along at the same time I was discovering (thanks to Nick-at-Nite) the MTM shows (“Mary Tyler Moore,” “Bob Newhart,” etc.). Ergo, even back then, my fourteen- and fifteen-year-old had a hard time watching “Friends” w/o feeling like television had come a long way down from what remain, for me, the classiest and most sophisticated TV comedies ever.

Hi, Rashad! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Your original comment was held for moderation. This site has an aggressive spam filter and holds replies from first-time commenters or users who look like first-time commenters (because of a change in email, name, IP address, etc.). If it happens again, don’t worry — I see everything that gets posted here, even the obvious spam.

I think FRIENDS’ pronounced commercialistic tendencies and youthful bent suggest a lack of class and sophistication that the show never goes out of its way to disprove. (I wouldn’t try to either.)

But as for how it compares to the MTM comedies of the early ‘70s, which are most notable for their excellent, ideal use of character, I think it’s a mistake to underestimate FRIENDS. Indeed, its ability to get a dedicated audience emotionally invested in its regulars was key to its longevity.

Yes, I don’t think it was ever as character-driven as the best MTM comedies were — the rom-com tonal conceit led to arcs that drove character, as opposed to the inverse — but all of the regulars were well-defined and could motivate laughs specific to their established personas. So, on an episodic level, the characters were well-realized and (mostly) well-used.

On more macro terms, the series also made it a point — for the first half of its run, anyway — to progress and evolve its regulars, preferring plots that, for each character, could provide exploration or growth related to their individual super-objectives.

So, I think, basically, FRIENDS did prioritize character in the same way that the MTM shows did; it just had additional goals that either clouded this fact or, at other moments, totally superseded them — sometimes to the characters’ detriments. You can bet we’ll be talking about those moments ahead; stay tuned…

friends was a good show and i think it’s a show that withstands the test of time. unlike some shows, it’s not political and it doesn’t really hit on current events. I know i can turn it on today and watch it without having to think back on what was going on in the early 90’s as i would have to with Will & Grace and Murphy Brown. the show worked because it was just the five of them. they had guest stars but most of the time the writers knew the best episodes were just about the five of them.

Hi, Sean! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I agree that the key to the show’s success is its characters (as always), and you’re right — most of the best FRIENDS episodes contend with a situation where the entire ensemble is together for an extended period of time.

But if you’ve read some of my past commentaries, you’ll know that I take a different approach than most when it comes to terms like “timeless” “test of time” and “dated.” I think every work is a period piece and I don’t hold the projection of contemporariness against a series; on the contrary, I find this a reason to celebrate. Also, while I agree that FRIENDS is less topical than the shows you mentioned, I don’t think that’s necessarily important to figuring out why it’s still successful.

We’ve seen topical shows that have syndicated well, like THE GOLDEN GIRLS (which is filled with references and jokes to famous people and current events), and ones that haven’t, like MURPHY BROWN (which, for a period of its run, prioritized a narrative agenda above its characterizations). As (I hope) my coverage indicated, the reason for those disparate legacies had less to do with their topicality as it did their treatment of character. THE GOLDEN GIRLS was brilliant in this regard, and MURPHY BROWN wasn’t. That’s all there is to it.

Like THE GOLDEN GRILS, people connect with and are attached to FRIENDS’ regulars. That was true then, and it’s still true now. As you noted, when the show simply focuses on (the six of) them, that’s when it finds many of its best episodes. Stay tuned for more…