Welcome to a new Sitcom Tuesday! This week, we’re continuing our look at Everybody Loves Raymond (1996-2005, CBS), the best “family” sitcom from the turn of the century.

Everybody Loves Raymond stars RAY ROMANO as Raymond Barone, PATRICIA HEATON as Debra Barone, BRAD GARRETT as Robert Barone, PETER BOYLE as Frank Barone, and DORIS ROBERTS as Marie Barone. With MONICA HORAN as Amy MacDougall.

With Season Seven, Everybody Loves Raymond enters the period of its run that I’ve called its third trimester, the “continuing” phase — a term that rightfully implies both resignation and triumph. Resignation because, after a long period of “discovering” led to three near-perfect years of “being” — during which the show was regularly capable of projecting its identity via weekly stories that either played to the central thesis or fostered an energy of existence that relished in the boldness of conflict that made thesis-playing more conducive — the series is now no longer able to operate as it was premised to dramatically function, which means it can therefore never claim to be as dramatically satisfying as it was before. The golden years have passed and they’re not coming back… But there’s triumph in this trimester, too, because in the very act of continuing — for three more seasons — Raymond also finds a way of going forward, all the while maintaining a level of quality that, though definitely not at peak form, is still strong enough to make this era the envy of long-running sitcoms everywhere… So, I want both understandings of “continuing” to be remembered in the coverage of these last three years. Keep them in mind as Seven tries to carry on in the wake of a basically fulfilled, meaning unusable, dramatic thesis, before finding what is, likely, the smartest distraction and narrative replacement possible; Eight attempts to widen its purview and enjoys exploring the relationships as they now exist within an expanded ensemble; and Nine dedicates itself to making every story count — for character, for the relationships, for the series — before concluding with a respectable series finale. As we’ll see, each of these years is different and brings something uniquely valuable to the table — the common denominator being a handful of classics and an ability to boast a generally fine baseline of quality — even though none truly make us ignore the overarching truth: the middle three seasons were better, with more gems and better gems. And this last era indeed has collective shortcomings that reveal why.

En masse, this last trimester sits at a higher pitch than the previous, and despite having seen the show, as it entered its peak era, heighten in tandem with its characterizations — chiefly those most involved with the thesis — and then noting, during Seasons Five and Six, an elevation in the show’s comedic sensibilities (it became more aggressive in the quest for bigger laughs), that’s all nothing compared to these final years, where everything is bigger than before: the performances, the situations, and even the characters. Now, I’m not bothered by the performers ratcheting up their energy — that’s part and parcel of elevated situations — and, to reiterate, I also don’t find it fruitful to spend much time harping on the broadening of the characterizations, for, like I said, “I think Raymond, generally, endures this broadening admirably, keeping the relationships defined and relatable, if slightly extended.” That is, the changes to the characters from bigger stories and for bigger laughs is not as troublesome on this series as it is on most (from the same era, take Frasier or Friends for comparison), as the characters themselves aren’t really hurt in the process. Are they exaggerated and therefore less realistic? For sure. But their relationships, by this point, are crystal clear, so that even as the regulars become less true, they’re still bound within our understanding of the ensemble dynamics and how they fit as a family. I’d rather reserve my criticism on this front for the heightened situations — the stories — for I think they’re most endemic of the problem with the final trimester: the inability to make meaningful narrative use of the central conflict within the show’s premise, and the relationship that most allows it to play towards its established thesis (which was what defined the peak years’ excellence). For in being unable to craft great Debra vs. Marie stories with the regularity of the peak era, the show’s whole identity is, for the first time in a while, palpably not assured.

And this isn’t only Seven’s fault. It’s mostly Six’s, as that year concluded with a three-parter that took the matriarchal tension to new heights, giving their rivalry a narrative prominence that could never be matched, creating an arc that was the dramatic apex of the central conflict and rendering it thereafter impossible to explore anything else as worthwhile between the two. You see, once their feud was used for Story (Capital S), how could it be used for story (lowercase s)? The pronounced plot’s very existence was thesis-fulfilling, even if the emotional catharsis was foolishly denied and prolonged for the sake of a cliffhanger. Thus, Seven was primed for a let-down, and it delivers one immediately in its broad and gaudy idea-based premiere, which decides to wrap up the now-drawn-out antagonism with a HIGH-OCTANE plot that uses the pair incidentally, instead turning to Ray and Robert to carry the action. It’s dreadful — both because Six made the mistake of putting a summer in between build-up and resolution, thereby diluting the tension, and also because the year seemingly wants to dilute the tension, for the show has to continue, meaning that this can’t be the big climactic moment it, by design, should have been. Also, while the year hopes to pretend things can go on as usual, it appears to know that the premise-perfecting nature of that arc, which has basically satisfied the thesis even though the actual resolution was lacking (because, again, the arc’s very existence is climactic), has precluded scripts from using the central conflict in weekly story. The pair’s minimal usage in the premiere is predictive once it becomes clear that there’s real trouble; only one episode this year — “The Shower” — actually uses their contention explicitly. And in order to do so, the entry’s story becomes so heightened and situationally stretched that we’re made to see what happens when Seven tries to out-apex an apex: implausibility, with strained character integrity.

So, the show is now without a functional story-making thesis. And this is unsatisfying due to our constant need for premise reaffirmation and because Seven flounders trying to fill the void. Naturally, it turns to heightened plot — Victories In Premise with comedically aggrandized ideas (like Robert dating a bug-eater in “She’s The One”) that derive their biggest hahas not from the characters, but from situational peculiarities. In fact, this year is loaded with entries that undermine the show’s reality — which typically comes from the core relationships — in favor of more conventionally “sitcom” story beats (like the play-acting resolution in “The Cult” or the contrived immaturity needed for “Who’s Next?”). This trite, leap-requiring “go along with it” sensibility will persist throughout the entire trimester, even though Seven — primarily the first part of Seven — is the only stretch without a substitute focus, making it the first period since the premise-ignorant first trimester where the show lives or dies based on episodic merits, and relatively speaking, doesn’t live every week. And this is why I think one could make an argument as to this being the weakest of the final era, for no other year has the unsurety of early Seven, where the show nominally tries to use its regular relationships for plot — turning often to Ray/Debra and even aiming to cultivate increased viability for their friends Bernie and Linda (what is this, Season One?) — only to instead turn to identity-ignorant, character-resistant ideas that we could find on any early ‘00s domestic comedy (see: “Homework” or “Robert Needs Money”)… However, maybe Seven isn’t the worst; I mean, Eight and Nine aren’t without issue. Eight offers fewer gems and more middlers, and Nine is very episodically predicated, with bigger story pursuits than any year preceding. And, actually, Seven kicks out the most classics (quantitatively, not proportionally), including “Baggage,” the series’ best Ray/Debra show. And while Eight and Nine benefit from something a good chunk of Seven doesn’t have — new ensemble dynamics — Seven is the year that makes the next two possible.

Yes, I’m talking now of Robert/Amy, and here Seven deserves a lot of praise, for as I said, turning to Robert — as the show has done before when it needed a distraction — was the smartest option. After all, his quest for independence has been a mirror to the thesis of Ray being trapped between two sides of the family, as Robert is stuck between the Barones he grew up with and the Barones he could potentially create. Sure, arcs about him are not thesis-affirming, not even marginally, but they’re character-based and allow for stories that don’t entirely seem out-of-place within the series’ thematics. Additionally, it was wise to have Amy be “the one,” because she’s well-established and defined — relatively uniquely, too — and we’re already “in.” So, when this plot finally goes forward — reunion in November, proposal in February, wedding in May — we’re immediately reacquainted with a dramatic engine that, in place of a thesis, provides purpose… Of course, unlike Seasons Eight and Nine, where Amy is a full-fledged member of the cast, and there’s more of a natural attempt to open up the premise to make better use of these new dynamics — which don’t actually change the central conflict or present anything as dramatically sharp, but merely allow for new story that plays as a result of widened character interests (thus providing the show with something of a new focus) — Seven is less lucky: it only benefits from the arc when in plot… Yet that’s in keeping with a year that, as we noted, is episodic with all its merits — merits that extend to other particulars too, like casting. And, ah, here’s where Seven warrants even more praise, for it not only introduces new conflict-providers in Amy’s family, but casts them beautifully with Fred Willard, Georgia Engel, and Chris Elliott, who make the most of their characterizations. We’ll talk more about this below, but every episode in which they appear is made better because of them, and they represent a charm specific to this comedically emboldened final trimester.

In fact, one of the things the MacDougalls do is suggest something that Robert/Amy alone can’t: a real narrative take on the thesis, for as most of Seven’s stories try to keep Ray’s centricity, the contrast between the Barones and the MacDougalls inevitably puts both Ray and Debra in the middle, mirroring the original drama of Ray being caught between competing family interests. Again, it’s not quite the same — he’s not as emotionally invested, so neither are we — but it makes for realer material than, say, “Who’s Next?” And there’s no denying: the MacDougalls are an episodic presence and a qualified boost, not a full dramatic salvation; even when they do appear, this thesis-forward design is no guarantee. (Heck, it’s rare.) But, as a whole, their inclusion — along with the Robert/Amy engine itself — provides Seven, and the rest of the “continuing” era, with a terrific example of how a comedy can make itself stay enjoyable late in its life, even after it’s outlived a narrative purpose. For even though there’s trouble on this front that never truly subsides — the show will never regularly function as dramatically premised again — these years remain funny, turning out a few annual classics and delighting with characters that, story interests aside, remain basically relatable. And, despite all the problems caused from a missing central conflict, this year finds the means by which the show is able to continue on… and it does so, with a maintained degree of quality. (Seven is actually among the most popular. I’m convinced this is because its serialized Robert/Amy engine is inherently digestible and emotionally engaging — like most arcs: Murphy’s pregnancy, Niles/Daphne, Jerry’s pilot, etc.) So, I think Seven really is a triumph, especially compared to the show’s long-running contemporaries, and this year’s major Emmy wins — for Roberts, Garrett, a script, and for the first time, the SERIES — are a reflection of Everybody Loves Raymond’s ability to still be so good this late in its life, when most shows aren’t. That’s, frankly, a big deal, and I have, as usual, picked ten episodes that I think exemplify the year’s finest.

01) Episode 148: “Counseling” (Aired: 09/23/02)

Debra takes Ray to marriage counseling and then regrets it.

Written by Mike Royce | Directed by Kenneth Shapiro

If there’s any episode on this list that most belongs with the Honorable Mentions, it’s this early one from the period in Season Seven that suffers most for the absence of a dramatic thesis (because there’s not yet the narrative engine of Robert’s love life to take our focus). Yet it’s a great study of the year’s early failings, for as noted above, it’s a Ray/Debra story that includes Bernie and Linda (empty characters who have no value due to their limited definitions) and utilizes a conventionally sitcom premise that we could see on any series: the main couple going to counseling. Accordingly, the character-starved plot demands a heightened mode of playing, where reality is stretched for the sake of compensating laughs — making it, again, a great sample of the year. What makes this entry palatable, however, is both the relationship focus (I mean, the Ray/Debra bond is weightier than any one regular), and some of the more character-specific moments scattered throughout the hyperbolic teleplay — like the enjoyable, if too on-the-nose, realization that Ray wants a wife like his mother… a roundabout comment on the muted thesis and an excuse for a sight gag involving a cardboard cutout bride. So, “Counseling” takes its place here because it’s the best representation of Seven at its lowest.

02) Episode 153: “The Sigh” (Aired: 11/04/02)

Ray gives Debra her own bathroom… and then regrets it.

Written by Steve Skrovan | Directed by Jerry Zaks

Among the series’ most memorable Ray/Debra shows, I think this one pales in comparison to an outing later in the year that has the distinction of being the couple’s absolute best. (No spoiler: you know I’m referring to “Baggage.”) That said, I also think this is an amiable dry-run — or wet-run, in this case — for that upcoming classic because it also takes advantage of a storyline that maximizes both characters’ similarly premised flaws to crescendo towards a bold slapstick centerpiece that’s indicative of the year’s comic interests, but still relatively satisfies because it’s well-anchored by the duo and the relatable tensions within their dynamic. While the upcoming Ray/Debra gem will better involve the family (and feature a premise more narratively unique), this offering must still be commended as a relationship-based show from a time in Season Seven, specifically, where these are our only saving grace. To wit, this is the best from the first third of the season’s output, and as much as I say that to compliment “The Sigh,” it’s probably more of an indictment on its neighbors, which are relatively dire. To that point, this one is somewhere in between being a gem and just a solid above-baseline segment.

03) Episode 155: “She’s The One” (Aired: 11/18/02)

Ray sees Robert’s new girlfriend eat a fly.

Written by Ray Romano & Philip Rosenthal | Directed by John Fortenberry

An overrated idea-driven affair, this is a prime example of the episodically predicated material that we discussed above in the seasonal commentary, for the bulk of this installment’s appeal is derived from the comedic notion of Robert’s girlfriend eating a fly. Oh, yes, the show tries to keep Raymond in the center by having him witness it (much to Robert’s disbelief), but there’s no denying that what we’re finding amusing is the premise, with the characters’ reactions being a peripheral bonus. Now, I don’t like this kind of storytelling and I don’t think it serves Raymond, this charactery and relationship-based series, very well. However, while I’m not necessarily able to celebrate this one as vociferously as most fans, I can still acknowledge that it was a “must-include,” for the boldness of its comic idea, the hilarious manner with which it’s executed — that is, if you’re going to seek out a story like this (which is no different from that strange Drew Carey that aired in October 2002 where he dates a woman obsessed with squirrels — see here), this teleplay carries it off as well as can be expected — and, lastly, the ultimate jewel it delivers: the return of Amy, which soon means a purpose for the year.

04) Episode 156: “Marie’s Vision” (Aired: 11/25/02)

Marie gets glasses and everyone becomes self-conscious about her observations.

Written by Jay Kogen | Directed by Sheldon Epps

This is the point where things start to turn, for now that Robert and Amy are reconciled, we’re just waiting for the next Sweeps period to come progress their relationship, giving us a narrative focus with an emotional pull that can serve as a distraction from the broad and less enjoyable fare otherwise defining the season. But, this is another outing that I’m supposed to enjoy more than I do, for it’s a holiday show that gets all the family together — including Amy — and utilizes a solid premise that takes advantage of a known character trait (Marie’s “helpful observations”) by magnifying it and then showcasing what that does to the rest of the ensemble. And because it’s Marie, it also gingerly acknowledges the buried central conflict, which is always appreciated… But yet, if the above was an unideal story with a strong teleplay, this one may be an example of the opposite, for the jokes are gaggy, and the substance — much of it forced in a scene between Marie and Frank (this is Peter Boyle’s “please give him an Emmy” year) — isn’t well-hitched to the folks to whom we want it hitched. And so the narrative isn’t as smart for the series as one guesses it’s intended to be. Oh, well; its head is in the right place. (Also, this was one of the entries for which Roberts won her third consecutive Emmy.)

05) Episode 157: “The Thought That Counts” (Aired: 12/09/02)

Ray promises Debra a Christmas present more special than what he just gave Marie.

Written by Tucker Cawley | Directed by Gary Halvorson

Okay, now we’re starting to get into the good stuff, for this unique Christmas installment throws back a bit to the past while simultaneously looking forward to the future. Let’s start with the past; the premise of Ray promising Debra a Christmas present that rivals the thoughtfulness of the gift he just gave Marie for her birthday is another acknowledgment of the central conflict and the thesis, for these two women are in competition and Ray is caught in the middle. That’s a prime dramatic foundation for story and it’s somewhat surprising to see it used here. At the same time, it looks to the future because the narrative isn’t really about the premise — it’s about what happens when it’s revealed that Robert was the source of Ray’s wonderful gift to Debra, and the one he got for Amy was far lacking in comparison. This leads to interesting — and fresh — dynamics that resemble the kind of relationship-based material we’ll see next season as the show uses its new regular (Amy) to explore the family in different, sometimes new (sometimes not) ways. For Season Seven then, “The Thought That Counts” is the list’s best reflection of the year’s liminality — kicked off the peak, but moving towards a definite future.

06) Episode 160: “Just A Formality” (Aired: 02/03/03)

Amy’s parents refuse to give Robert a blessing to marry their daughter.

Written by Philip Rosenthal & Steve Skrovan | Directed by Gary Halvorson

Of course the show that introduces Fred Willard and Georgia Engel (and Chris Elliott) is going to be discussion-worthy. Fortunately, it’s good enough to make the list (and even be something of a classic) too, for even though the engagement is a big event that allows story mechanics to overtake the simple exploration of character, the story itself yields forward movement in Robert’s emotional arc, which has been stalled and used in fits and starts whenever the series needs a temporary distraction. Now that the momentum suggested by this plot gives the season a dramatic purpose that was sorely lacking before, we not only welcome the story, but we’re also more able to enjoy all the riches it provides, including the casting of that spectacular trio, including Elliott, who takes over as Amy’s brother (from Paul Reubens, who played him once in Season Four’s “Hackidu”) and is a vital presence on the show because he makes Ray’s involvement easier. And since the lead’s centricity remains somewhat of a necessity, this is a stroke of structural genius — not to mention the fact that it adds dimension to the MacDougalls, whose mild-mannered devout sensibilities would otherwise seem more gimmicky and less nuanced. (Note that Brad Garrett won his second Emmy, in part, for this one.)

07) Episode 163: “Meeting The Parents” (Aired: 02/24/03)

Amy’s parents meet the Barones during a Sunday brunch.

Written by Mike Royce & Lew Schneider | Directed by Jerry Zaks

The only outing here that could rival my chosen MVE for that distinction, this is the dramatically seminal show where the Barones meet the MacDougalls. The definitions prescribed to Hank and Pat in the entry above primed them for a combustible first meeting with the family, for as with Debra’s parents, “the in-laws” are comedically used as a study in contrast. While the Whelans’ differences from the Barones were based on class and the sophistication or worldliness that implied (particularly regarding parenting skills and emotional availability), the MacDougalls offer something more foundational: wildly opposed temperaments — the quiet and devout meeting the loud and irreverent. It’s a simpler, more clash-driven design, but that’s almost a given, for this trimester demands characterizations more primed for conflict, and thus humor, and the MacDougalls are therefore a great representation of the era’s comic capabilities — which, sure, are broadening by the year, but nevertheless stem from the thesis-adopting traits we saw at the start of the previous trimester… Speaking of the thesis, this is one of those rare stories — this is the year’s only example — where the presence of the MacDougalls allows for a variation on the original conflict, for with the two families figuratively warring, Ray and Debra are caught in the middle, and it’s up to them — Ray, especially — to make things right. Once more, I can’t say it’s emotionally as satisfying as the pilot’s intent, but it’s thematically acceptable, and in an excursion like this, with big laughs and big drama, a solid foundation is incredibly valuable. Doesn’t disappoint. (Also, for trivial purposes, this is shown in a reverse order with “Sweet Charity” on the DVD because it was intended to air the week before. I believe it was switched because of FOX’s Joe Millionaire finale. CBS and Raymond wanted to save this important show for a less competitive week where more people would see it.)

08) Episode 164: “The Plan” (Aired: 03/10/03)

The men convince Robert to screw-up the wedding invites as a ploy to avoid responsibility.

Written by Tucker Cawley | Directed by Jerry Zaks

Probably the most fun of all the wedding-themed segments, “The Plan” is much like “The Thought That Counts” because it foretells what we can expect to see more of in the upcoming seasons. Here, in this rich ensemble-focused entry that has Ray and Frank persuading Robert to purposely screw up the wedding invitations so that he can get out of doing work in the future, a new story template arises: the men against the women. Although previous years have flirted with this concept before, it isn’t until Amy comes along to provide an even-gendered split among the regulars that the familiar narrative pattern really gains any credence (though, as we’ll see, it won’t be overused). You’ll notice that these shows don’t make great use of the dramatic thesis, but in the third trimester, as we know, other episodic story sources are required — and this is one such design that allows the series to remain firmly ensconced within the regular family ensemble, using relationship-based stories that keep Raymond in the center, even if they’re nominally about Robert and Amy. The kitchen scene — nothing new to us — is something we’ll truly see a lot more of on this series in the last two seasons, where the all-cast combustion almost becomes a structural requirement. Now, it’s still exciting and well-earned — thanks, in part, to a funny and novel teleplay that could only exist in Seven.

09) Episode 167: “The Shower” (Aired: 04/28/03)

Following a fight with Marie, Debra is arrested for falling asleep drunk behind the wheel.

Written by Leslie Caveny | Directed by Jerry Zaks

While the above suggested a new narrative template for the series, “The Shower” reveals precisely why new templates are needed, for this is the only offering in all of Seven that explicitly, with no pulled-punches, bases its story around the muted central conflict between Debra and Marie. And as the only one that directly deals with their dynamic, it’s something of a “must-include” on dramatic principle, even though it reveals some of Seven’s worst qualities, and makes the case as to why the year simply couldn’t use the thesis’ central conflict any more often that it does. For as noted in the seasonal commentary, the sixth year’s dramatic Debra/Marie feud was the apex of their tension and represented a peak that couldn’t be topped. But in reigniting their tension, this story indeed tries to top it — through a heightened premise that’s meant to yield big, gaudy hahas by pushing the manic Debra to her limit, but is instead a testament to how dramatically fulfilling and conclusive the previous arc was in relation, and also to both how story-driven and unappealingly broad the show has become since then. Additionally, this one shows, unfortunately, that the year had no choice but to exacerbate those traits if it even wanted to use the thesis, making it a Catch-22, for as the terrible “on-any-sitcom” notion of Debra being arrested — seriously, sitcom characters in jail is one of the most tired story-driven clichés you’ll find (we take a big leap with it) — is typical of this rudderless year, it’s also true that such foolishness must be used to reach the emotional heights needed to wake up a sleeping conflict. Accordingly, I find a lot of this episode sad, for it tells us, in no uncertain terms, why the third trimester could never be as fulfilling as its predecessor.

10) Episode 168: “Baggage” (Aired: 05/05/03)

Ray and Debra have a contest of wills over an unpacked suitcase.

Written by Tucker Cawley | Directed by Gary Halvorson

Without a doubt, this is the best Ray/Debra show of the entire series, and as teased, it’s my choice for the season’s finest (MVE). It’s inspired by true events, as many of the best Raymonds happen to be, with a uniquely premised, but thematically relatable conflict involving a piece of luggage — or baggage (with all its double meanings) — and a clash of wills between the central couple that speaks exactly to what this era wants to say about their relationship: that they’re more alike than not. You see, earlier seasons, when the series was more attuned to its central conflict, had to keep Raymond trapped by the ping-ponging interests of his families (usually represented by Debra and Marie), and it was necessary that the main couple’s dramas somehow existed in relation to that core tension, meaning that often the differences between Ray and Debra were the source of their comic disagreements. But now that the show has moved away from that, focusing episodes on their relationship more acutely — all the while preparing for an ensemble in which they’ve got to be stuck in the middle of conflicts that don’t involve them as active agents — it’s become more fun, and more narratively necessary, to pair them and illustrate their mutually shared flaws: the very reasons that they, structurally, make a good twosome.

That’s something Cawley’s Emmy-winning teleplay does beautifully — and in essence, it’s a Ray/Debra show that’s designed explicitly FOR the third trimester. More than that though, it’s a culmination of all their shows of late, which have tended to build up to big slapstick centerpieces from initially relatable scenarios. This installment has both the best big slapstick centerpiece and the best initially relatable scenario, and in comparison to the earlier “The Sigh,” which I think can be seen as a less-realized version of this gem, “Baggage” also extends its Ray/Debra interests to the series at large, for in its smarter involvement of the others — particularly here with Marie, who bonds with Debra over a feud she’s been having for decades with Frank over the big fork and spoon (an iconic image for the series) — the entry not only makes a slight acknowledgement of the central conflict (because any time these two women bond, we’re reminded that they usually don’t), it also recognizes Ray/Debra’s place in the ensemble and how it’s starting to shift out of necessity. (This is in addition to the basic fact that it’s another example of the season’s heightened comic intentions and gaudier story pursuits — including a small, but rare flashback — making it typical ostentatious Seven.) In this way, “Baggage” isn’t just the best Ray/Debra show, it’s a smart statement on the series — where it’s come from and where it’s going. The choice for MVE this year was more obvious than ever.

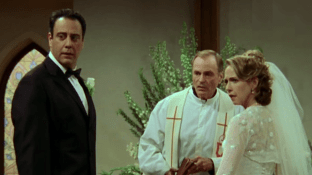

Other notable episodes that merit mention include: “The Disciplinarian,” a parenting entry that once again showcases how Ray’s upbringing has influenced who he is today, thus putting him in a central position that tips its figurative hat to the thesis, and “Robert’s Wedding (II),” which officially — as seen in syndication — begins after the break where Marie stands up to interrupt Robert’s nuptials. (The original telecast was extra-long; in syndication, the show is split in two, with Part I buttressed by a segment of Robert/Amy clips.) Truthfully, this big dramatic scene — a heightened and over-the-top moment that reveals the year’s comedic interests, but nevertheless stems from what we know of Marie and therefore doesn’t seem totally ridiculous — is the least disappointing thing about this offering, which is otherwise a big event with a little more bloat than substance. (Naturally, the Television Academy couldn’t resist it, and awarded Garrett and Roberts their statues, in part, for this season-ender.)

*** The MVE Award for the Best Episode from Season Seven of Everybody Loves Raymond goes to…

“Baggage”

Come back next week for Season Eight! Stay tuned tomorrow for a new Wildcard Wednesday!

yes baggage is one of my favs and def the seasons best

u picked all the right ones this week i think but maybe thats also cuz there are less real good picks

better then 8 / 9 tho

Hi, BB! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I go back and forth about which season in the final trimester is my preference. As noted above, they each have respective strengths (and weaknesses). Stay tuned for more…

Spot on commentary this week, Jackson! I love the McDougalls, but I’ve always said that S7 was just as rocky as S8 and S9, which most fans if they acknowledge a descent in quality at all point to as being weaker. But S7 has its own issues and in the beginning especially with so many dissapointing episodes.

The talk of the thesis and the Marie v. Debra conflict over the past few weeks really got to me and explains why the first part of the year is so hit and mostly miss. It’s the worse stuff the show produced since S2!

I think you hit it right on the head with the list too. I don’t know which episodes I would have picked differently, probably none. “Baggage” is amazing and the best from this final few years IMO.

Hi, Nat! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Yes, the first part of Season Seven is an extended low that not even Season Eight or Nine can claim! Stay tuned…

Wonderful commentary as usual. Really enjoying your take on this series.

Hi, Deb! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I’m so glad you’re enjoying these posts!

Have to echo what great picks there were this week. You’re right that there aren’t as many excellent episodes this week as in the past few seasons. But I am not as down on the year as you because I still think it’s better than the final two. And I say this as someone who doesn’t mind the last two either but think they don’t have as many “gems.”

Hi, Elaine! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I go back and forth about which season in the final trimester is my preference. As noted above, they each have respective strengths (and weaknesses). As for Season Seven, I think in terms of quantity, it’s the year (of the last three) that comes the closest to replicating the volume of gems produced annually in the peak era. But Seasons Eight and Nine aren’t without some goodies, either; stay tuned…

I don’t disagree with any of your picks for this year. What are your thoughts on Debra’s characterization in the final trimester?

Also, I do apologize for my assumption on the season six page. It was not my intention to pigeonhole your work, and I do appreciate your clarification.

No need to apologize! I mostly wanted to make sure that I was being clear with my thoughts on real-time and why it’s a recurring presence here. Your comment was merely a chance to expand on some of the rhetorical stuff we discuss week-to-week and further explore my own thoughts. No offense taken (or meant on my end — I saw a soapbox moment and took it).

Hi, Charlie! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Good question. I think this heightened era heightens ALL the characterizations, and as noted, they all become generally less realistic, with each season progressing this trend so that the ninth, of course, is the most glaring offender. (We’ll talk a little more about this in that post — in fact, I give an example of a story where Debra, in particular, acts more like a “sitcom character” than a human.)

But as we’ve discussed a bit already, I think that’s a peripheral concern to the cause of this trend: the era’s aggrandized nature of story (which is often idea-led and situational), and while I understand that there’s a school of thought that likes to charge Debra with becoming increasingly shrill and angry in later seasons, I actually don’t think she heightens any more than anyone else, and so I’m no more bothered by her depiction in this era than I am by say, Robert’s or Ray’s.

Rather, I think Debra simply doesn’t get the same strong character showcases that she had in the middle years, now that the central conflict is no longer regularly utilizable. And to that point, she doesn’t get as many chances for comic excellence since her corresponding dramatic relevance has been minimized. Thus, I think the era lets her down far more than she lets down the era…

…And if some fans notice her broadening more than they notice the others’, I’d argue that this is simply a function of stories not being able to use her as dramatically well as they used to. (See: “The Shower”)

Yaaaassss! “The Baggage” is one of the finest sitcom episodes of the past 20 years! Heaton rocks it and I love the use of the Deb-Marie stuff as you said.

Hi, Eboni! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Yep, it’s one of RAYMOND’s top-tier finest!

I’ll comment more on season seven later (and on seasons five and six–I’m way behind) but I’ve got ask this question now: Patricia Heaton submitted “Baggage” for Emmy. I think she’s typically wonderful in that one but she lost the Emmy. I think had she submitted “The Shower” she would have won. In that one she’s especially vulnerable and funny. And as you say, Jackson, it’s a classic Debra vs. Marie episode. Your thoughts? What do you think is Ms. Heaton’s best episode of season seven?

Hi, Mark! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I think a lot of factors go into Emmy wins, but at the end of the day, it’s just a group of industry insiders choosing who they want to honor from a given selection. I think tracking the awards is notable most as a matter of historical record — and because they *can* indirectly influence our search for quality (if wins result in changes to the show: character prominence/usage, timeslot swaps, increased budgets, public perception, etc.)… But I don’t believe they’re determinant of what’s good; we have to decide that for ourselves.

As for Heaton’s best work this season, I think all actors are served best by having the best material, and the best material this season, by my estimation, is “Baggage.” It’s not even close… Now, if Debra wasn’t dramatically or comedically well-featured in that story, I could understand why the actress would have made another pick. But she *is* well-featured; in fact, as I said, I think it’s the BEST Ray/Debra episode of the entire series — not to mention the best of the season (for reasons shared above).

To that point, I included “The Shower” in this list on “dramatic principle,” but I also said that it “reveals some of Seven’s worst qualities,” has “a heightened premise that’s meant to yield big, gaudy hahas,” and features “one of the most tired story-driven clichés you’ll find.” In other words… I consider it far from the year’s best, and I don’t think it showcases Heaton better than “Baggage.” (Heightened stories make for heightened performances; as stated above, I blame the stories, not the performances, but this relationship still stands.)

However, I think it’s mostly moot; episodic selection probably didn’t matter much that year anyway… For with every nominee in the Lead Actress, Comedy category coming from established series with which Academy voters were already well-acquainted, I don’t think sample reels were of significant importance in deciding whose turn it was to be recognized. Everyone knew, by then, who was doing what.

Loved “Baggage” and “The Shower”. I also enjoyed the addition of the MacDougalls. I can’t wait to see what you think about “P.T.& A.” and “The Power of No” both from season 9. These are two of my favorite episodes. Thanks again for all you do.

Hi, Smitty! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Well, I don’t like to spoil upcoming selections… but I feel like I have to brace you now for disappointment.

“P.T.& A.” and “The Power Of No” are both Honorable Mentions for Season Nine — in fact, I’ve actually alluded above to one of those episodes in this here comment section — and, as with every show in the final year, I’m afraid these decisions weren’t difficult. Stay tuned…

Season 7 is the second consecutive season when the MVE is one that is so clearly identified, which is saying something, given the relatively large number of classics in Season 6 and even in S7 (I am a particular fan of “The Plan”).

But, to me, as well as to you, “The Angry Family” and “Baggage” ARE the best episodes of these two seasons–even as Season 6 seems to be the best year of the series–and that begs the question: Are they the two best episodes of the entire series? Does any episode belong above either of them?

Hi, Guy! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Good questions. But to answer, I have to start from a different premise.

I actually think it’s been easy to select an MVE for *every* season of EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND because the analytical framework of this coverage has made each year’s choice obvious. In the first three, the best entries built the show and reflected their season; in the middle three, the best entries embodied the show and reflected their season; and in the last three, the best entries — true to an episodically predicated era — episodically elevated their season, with some thematic reflection in support.

Thus, I don’t think the MVEs for Seasons Six and Seven were any more clear-cut than they were for any other, including the ones that came before and the ones that are still to come.

From there, I think it’s important to make a larger point: “The Angry Family” and “Baggage” are entirely different episodes and they warrant a greater degree of disassociation. (In fact, they’re SO reflective of their separate eras that they’re great examples for why this trimester concept even holds figurative water.) Comparing them too freely obscures why they individually work so well.

Let’s separate them and start with “The Angry Family.” I definitely think there’s no better episode than the best from the best season. (I know it seems obvious when stated as such, but actually, this is not always true. Example: FRASIER.) And I consider “The Angry Family” the strongest because, true to the peak era, it’s the finest encapsulation of both the series’ identity and the year’s own comic interests, and in being the best of the best of the best, it’s, simply, the best.

As for “Baggage,” its charms are not so all-encompassing. It doesn’t tell me as much about the series’ identity — and that’s okay; I’m not expecting that, because this final era, as we’ve seen, can’t fully do so. But it does tell me about the season — the focus on Ray/Debra, the use of Victories In Premise, the heightened comic sensibilities, etc. And I appreciate it for all the reasons expressed above, including the fact that, in pivoting Ray/Debra for a different function in the final trimester (which never serves them as well as “Baggage,” incidentally), the characters comedically and dramatically thrive in a way that’s unique and, I think, more exciting than anything else for them.

Also, in being the best episode for the series’ most important one-on-one relationship — the central couple — “Baggage” not only is the best of the final trimester’s output (and indicative of the year it comes from in particular), it’s also the series’ best look at a SPECIFIC part of the show’s identity. In this way, “The Angry Family,” true to its era, is the best of the series as a whole, while “Baggage,” true to its era, has to be taken on more limited terms, and finds its superiority in ways more confined and episodic.

Now… as to whether I find “Baggage” the second finest episode behind “The Angry Family,” I can only do so if I’m willing to accept that the former can’t be competitive in the same way that entries from the three years in the obvious peak era, like “The Angry Family,” happen to be.

You see, I inherently think the best scripts of any series tend to be the ones that explore the most within the established premise while revealing how the characters usually function. As such, if I were corralling a handful of RAYMOND’s finest (to show someone who’d never seen the series before), I’d pick the MVEs from the other two peak, series-reflecting seasons — “Debra Makes Something Good” and “The Canister” — before I’d pick “Baggage,” which is less valuable to the overall show than it is to specific elements: an era, a season, a relationship.

That said, if I were to meet “Baggage” on the episodic terms that this final era asks me to meet it, then I could definitely see how, behind “The Angry Family” — although farther behind “The Angry Family” than I could even suggest — it could be viewed as the next singularly strong half-hour of RAYMOND: uniquely premised, revealing for the characters, and wickedly funny (more so than almost all the other MVEs).

And off of these less series-driven, more *episodic*-driven metrics, I could answer your questions with: yes, these are the two best episodes of the series, and no, there’s none above them…

But, again, those answers immediately change in a context that, frankly, forces “Baggage” to be held to the higher standards more reflective of seasons better than the seventh, because — and, again, I don’t want this to be forgotten — these two years (Six and Seven) are from radically different narrative periods, and that’s obvious and not ignorable, for one is *clearly* better than the other.

To put a button on it with which I’m more comfortable: “The Angry Family” tells me that RAYMOND is great; “Baggage” tells me that “Baggage” is great.

Jackson,

Thanks so much for such a thoughtful response. I am glad that the question I raised gave you so much room to expound upon it a comprehensive answer.

I actually think that EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND–even though you have said that its final three seasons represent a considerable drop-off vs. the middle three–maintains its level of quality and vitality better in its later years than almost any other long-running sitcom I can think of.

The only series that still had its “fastball” in Seasons 8 and 9 (and beyond) to a greater extend than RAYMOND, in my mind, is CHEERS.

P.S.: I, too, love “The Canister” and it’s also very, very high on my personal ELR episode list.

Indeed. As stated above, despite criticisms that arise when comparing EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND against itself, the show’s quality in these final years still makes it “the envy of long-running sitcoms everywhere.” Stay tuned…

Believe it or not my second favorite season

Hi, Track! Thanks for reading and commenting.

I do believe it. Seven has always been popular, with the Robert/Amy narrative engine in the latter half sparking both an emotionally engaging plot-based momentum that no other season boasts and a handful of heightened Victories In Premise that resemble gems, suggesting a quantitative success that comes closest to matching the peak-era’s abundance more than any other season outside of it…

But as explored, Seven IS outside the peak era, and I don’t think that’s ever not clear, for while the year’s episodic charms, by definition, guarantee individual episodic successes, they don’t exist in a vacuum, and the corresponding failures (along with the *nature* of these successes) suggest concerns about the series’ overall health that most delineate this year from the three stronger seasons before.