Welcome to a new Sitcom Tuesday and the end of another two-week rerun series! Once again, I’m excited to resurrect a currently relevant post from this blog’s nearly eight-year run. As before, I’ll provide a link to the original piece and then offer a bit of updated commentary. But please be gentle. This early article is from my second year blogging, and standards have changed as I’ve changed — I’ve improved as a thinker, a communicator, and a television-watcher.

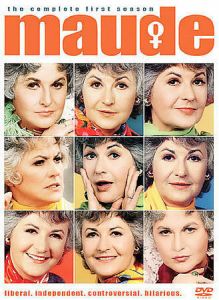

This week, let’s revisit… The Ten Best MAUDE Episodes of Season One: https://jacksonupperco.com/2015/03/17/the-ten-best-maude-episodes-of-season-one/

If this blog’s jump from That Girl to Maude seems abrupt, imagine how it would have felt to viewers in 1971, who saw the demise of almost every single sitcom staple from the 1960s and the meteoric ascendance of Norman Lear’s All In The Family, which quickly became the most-watched show in the country and even introduced the soon to be spun-off Maude Findlay, all in under 12 months. Now, we talked last week about the transitional late ’60s, which anticipated the medium’s shift towards low-concept realism in the early ’70s, and teased the sitcom’s adoption of contemporary “relevance,” a programming strategy created by CBS’ new network president Bob Wood and carried out by his second in command (Mike Dann’s replacement), Fred Silverman. Yet Norman Lear’s All In The Family is the kind of show that saw a cracked door and didn’t just open it, but kicked it down entirely, giving the rest of the 1970s space to be more overtly political (which was Lear’s interest), and also more narratively truthful, with a palpable humanity only bettered by 1970’s The Mary Tyler Moore Show, another multi-cam that joined All In The Family to offer a one-two punch of evolved standards for sitcoms, evidenced here and in all the shows that followed because of their success. These standards are my interest, for this trend towards truthful multi-cams with palpable humanity, usually displayed via well-defined comic regulars, speaks to why I call the ’70s, and the early ’70s especially, my favorite era for sitcoms. And while I’ve previously defined the MTM efforts as the next evolution in character-driven sitcommery (the kind seen on Dick Van Dyke and I Love Lucy) and Lear’s efforts as his decade’s contribution to the idea-driven alternative (derived from sketch comedy, in which he had experience) — for all his work is propelled by a guiding sociopolitical concern and everything from story to character to comedy are but tools to satisfy a central idea — both of these contrasting tent-poles share a comedic acknowledgment of contemporary life through modern settings, relatable conflicts, and low-concept premises that inherently have characters at their fore, forcing an elevated storytelling hinged around the cultivation of strong personalities capable of anchoring weekly plots that satisfy the overarching comedic/dramatic objectives.

In other words, even if Lear’s sitcoms don’t have “character” as their focus, in the same way MTM’s do, their wants and designs nevertheless need and emphasize comic definition for story-channeling leads, essentially meaning that, in this era, many of the idea-driven shows have great character work too (at least, on their best days). That’s why this period’s gems are better than other period’s gems, and why I count it as a Golden Age (in quality, not quantity). But before we begin next week discussing one of Lear’s classics, Good Times — which, yes, I know is far from his finest, but covering it now takes advantage of the work I did several years ago when studying the series in a professional capacity (see here) — I’m going to share some brief updated thoughts on his oeuvre, particularly with regard to character. However, I qualified that mission with “brief” because, honestly, I’m not-so-interested right now in revisiting the 1970s to the extent we just did with the 1950s and ’60s, and indeed, we won’t be “in” this decade for as long, because even though I consider it my favorite and naturally think my analysis of ’70s shows from 2014/2015 can’t hold a figurative candle to what I would be offering today, we’ve already covered the best of the best, and anything new I have to say about them can be said in posts like this. Oh, I know, I’ve skipped over some staples — like MASH, and all of Garry Marshall’s post-Odd Couple endeavors — but they’re not the best, and it’s debatable how much our study of the genre would truly be enriched by their inclusions, especially given my criticisms. (That said, I’m still considering several possibilities; stay tuned for more…) So, I’m keeping this short and sweet — this isn’t full coverage; I’m just setting the table for Good Times by putting it in an updated context with the previous Lear hits we’ve examined: All In The Family, which introduced the title characters from both The Jeffersons and Maude, the latter of which debuted a version of Good Times‘ Florida Evans and her husband. (Incidentally, Lear had minimal involvement in Sanford And Son; it was overseen by his then-partner Bud Yorkin, so it’s not a needed reference point this week — neither is Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, which isn’t a sitcom.) To begin, I have to say that even though I praised Lear’s character work relative to other eras, and other idea-driven shows specifically, his series are otherwise totally idea-driven.

That is, all of Lear’s comedies are built for a sociopolitical reason, and while they each have low-concept structures anchored by characters, their premises seek to address “relevant” themes in weekly story, with each lead designed to support certain notions while still, thankfully, earning laughs (as Lear’s motto is that a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down). The simplest and best example is All In The Family, on which Lear held the tightest grip. It’s also his strongest — the groundbreaker, with a door-kicking boldness that fuels its comedy and gives it the most dramatic novelty, for by premiering first, it’s ahead of the rest in addressing previously taboo topics, yielding a freshness that the others lack, especially once outside the conservative Nixon era, to which Lear was a liberal rebuttal. More importantly, Family has the best-defined regulars, courtesy of a very low-concept premise inspired by a British series — about a two-couple family of separate generations — that uses its leads to fulfill a political thesis, but simultaneously puts their conflicts in the context of an accessible human dynamic. You see, Lear’s objective is ridiculing the Nixon conservative, whom he depicts as Archie Bunker, a menacingly uneducated and crotchety bigot, resistant to modern realities and saddled with an idealistic but lazy younger liberal who challenges his beliefs in a relatably fraught familial bond: they’re in-laws. This makes both boldly defined, for although the holder of the viewpoint to which Lear is sympathetic is less extreme, they have a personal contentiousness that fuels their animosity and makes both perspectives clear. Similarly, the two women in the house offer an obvious study in contrasting gender norms — the subservient wife and the equal partner — but they’re caught between strong emotional bonds that transcend politics. So, while everyone’s distinct personality is determined by Lear’s guiding raison d’être, their roles in the family also provide positional perspectives that give human justifications to the socially pedagogical conflicts. This can actually make the show seem somewhat character-driven, but it’s not; while the character work is strong because of this emotional support, the guiding idea — of deriding half the country’s politics through an extreme depiction of one of its adherents — is driving how each regular is situated in the family and what stories they must allow. Thus, ideas are being explored, not the characters.

Maude, cultivated in 1972 to showcase a character introduced on All In The Family, tries to do the same, but in reverse: caricaturing the outspoken liberal through an extreme depiction that spoofs the similar folly of holding staunch, unwavering beliefs. Yet this proves more difficult, not only because the ensemble isn’t filled out as well with leads who can inspire topics to challenge her — made more glaring by Maude’s sheer dominance as a comic figure — but also because the show, and those writing it, agree with her perspective, making it harder to mock. (More below…) Meanwhile, 1974’s Good Times and 1975’s The Jeffersons have it much simpler — as some of the first Black-led sitcoms since the early ’50s (along with ’72’s more exclusively laugh-oriented Sanford And Son, of equal subtextual relevance but with less of a desire to shout it), they’re concerned with humanizing Black people on TV via contrasting experiences: the struggle of living in the Chicago projects, “the ghetto,” and, conversely, the culture shock a newly rich family faces when moving to the posh Upper East Side, a traditionally white enclave. In these shows, unlike, say, 1968’s Julia, Lear applies race to structures that emphasize resulting conflict (through comedy), and, again, with leads who support the thesis. While Good Times is a low-concept family show whose best stories examine the tensions that come from the Evans’ economically strained living situation, relatable not just to many Black people, but, from the continuity of their humanity, to all people, The Jeffersons’ best stories examine the tensions that come from being Black in a white world — or, from being outsiders — with emotional support through the characters and their relationships: a small business owner who’s now a mini-tycoon, his wife, a former domestic who now has her own domestic, and their interracial in-laws — a device that brings a white person into the Black family, mirroring the Jeffersons’ own dramatic conflict of trying to fit in. Naturally, both are simple homebound comedies that need relationships, and thus characterizations, to thrive — this is that shared ’70s ethos — but they’re packaged for a higher calling, and we’re primed by each to determine value not based on how well these relationships or characterizations are used to prop up comic story, but how well these relationships or characterizations are used to prop up premise–affirming comic story.

The problem is that, like all idea-driven shows, they inevitably run out of ideas that support the premise, and their characters, designed as idea-conduits, typically aren’t great idea-generators. We’ll talk more about Good Times soon, but suffice it to say, the later in the decade a Lear hit premieres, the weaker its affiliation with an overarching and intended relevancy, as the novelty of political topicality diminishes over time, leaving the characters alone to supply the value. This is a structure that should breed success, but while Lear has generally well-defined leads who have some humanity because of the issues they engage, as proxies for macro sociopolitical ideas, they have an accompanying bigness, a broadness, that aggrandizes comedy and drama. As such, when politically minded premise-affirming stories erode, these folks prove, despite their low-concept realistic trappings, that they’re more extreme than their surroundings. And as idea-channeling leads in idea-driven shows that no longer have the right ideas, they — left to their own devices — invite big stories that aren’t so believable, fueled by either heavy drama, which often arises in an attempt to reconnect with “relevancy,” or silly comedy, with larger-than-life centerpieces that don’t jibe with the realism once needed to ground premised topicality. We see this directly on The Jeffersons, which was never produced by Lear and is always broader than his usual, but starts in a dramatically truthful place and then grows disconnected from common sense alongside wild swings in tone that the characters can’t handle. (A similar extremeness is seen on One Day At A Time, which has more self-important, unmotivated drama than the yuk-yuk Jeffersons, making it less fun or worth covering.) As for Family, its strengths — like its novelty and simple character-forward design — all ensure that it’s able to hold on longer to relevant stories. Yet it too sees its thesis evaporate, forcing a reliance on the outsized humanity supplied from its stellar cast — and especially Carroll O’Connor, who actually makes Archie harder to deride because of his immersive portrayal — as stories vacillate between heightened drama and heightened comedy, with politics intermittently present and the leads generally funny, but not often capable of motivating these tonal shifts because, even with a personable design, they were made to be led by ideas, not to actually lead them. (See: Archie Bunker’s Place.)

Unsurprisingly then, All In The Family and The Jeffersons (and maybe Good Times — stay tuned) are only great when they’re able to count on substantive stories that validate their political intentions, filtered through characters who are solely designed as vehicles for them. The only outlier is Maude, which as noted, was set up with the trickiest politics, largely due to both a lackluster ensemble (including Bill Macy’s Walter) that wasn’t positioned well opposite its lead, and a counterintuitive premise of mocking someone whose views, while extreme, scripts saw as correct. Because of these challenges, the show knew it needed to pivot, and so, after a first year that was heavily “relevant” — and included the infamous two-part abortion episode written by Susan Harris (Fay, Soap, The Golden Girls) — Maude‘s second season, earlier than any of the other Lear comedies, enacts a painstaking campaign to reimagine its ensemble and better define its previously weak leads so that they can shoulder more of the comedic and dramatic burden for a dwindling political engine, turning Rue McClanahan’s Vivian into the leading lady’s sidekick and romantically pairing her with Maude’s neighbor and rival, Arthur (Conrad Bain), thereby creating a secondary couple that allows the series to indulge a classic sitcom construct, and plots that, while more traditional in this vein, nevertheless force a more forward use of the leads and their relationships. Oh, Maude’s outspoken liberality is still ingrained in her depiction, and these couples often fight “battle of the sexes” conflicts, but now said conflicts are better draped around cultivated personas and their interpersonal dynamics instead of the difficult comic objective of ridiculing the hyperbole of one person’s extreme liberal views. Simply put, Maude reinvents itself during its second season to become less political, more character-based. And you know what? It becomes a better show, tackling this inevitable problem when it still has the creative juice to establish a new baseline of quality hinged around its comic ideas, which aren’t totally character-driven (at least, not beyond the all-encompassing Maude persona, which remains dominating), but are at least funnier and more dramatically rewarding for character than their counterparts on other Lear shows, which waited so long to evolve that they were drained of good ideas meaningfully connected to the series’ givens.

In taking charge and explicitly developing its regulars, Maude self-corrects. Again, it’s not perfect — Maude still dominates everyone else in the cast and they’re all broader and less believable than MTM’s leads, while the leaps between comedy and drama are extreme and can be jarring — but it’s good enough to be much better than its single-dimensional political reputation has long implied, for there are some really funny half-hours, most of them in the more internally character-concerned third, fourth, and fifth seasons, following a transitional second year (which some like to champion as an aesthetic blend of the freshman collection’s overt politics and the middle’s more traditional comedy, but I see as too narratively focused on its own evolution to maximize its developing opportunities). Actually, the show can be broken down into three distinct eras, separated by Maude’s housekeepers. All of Season One and most of Season Two include Florida, the future star of Good Times, whose Blackness is used, per this initially political premise, to exploit Maude’s white guilt and mock the covert racism she exhibits by not treating a Black woman equally. At the top of Season Three, Florida is replaced by the bawdy and British Mrs. Naugatuck (Hermione Baddeley), whose “serve the master” mentality is initially suggested as a point of contention for feminist Maude Findlay. But this political understanding of Naugatuck quickly gives way to the comic details of her exaggerated personality, indicating the series’ move to a more character-rooted sense of humor and mode of storytelling, which lasts until her departure at the end of Five. And finally, the sixth season boasts another Black housekeeper, Victoria, whom the show calls upon in the midst of an identity crisis where it’s basically run out of funny ideas for these leads to support and therefore hopes a resurrected racial drama will provide narrative fodder and a return to the series’ roots. It’s too late though; Maude has always been a show built around ideas, and even when it turned to its characters and their relationships for help with its comedic/dramatic narrative needs — and away from its leading political purpose — this wasn’t done to explore the characters, but to find material divorced from the premise. Thus, character is, again, merely a vessel for ideas.

And even though Maude, like all of Lear’s efforts, needs strong characters, and often features them well (better than so many from this and other decades), everything it does is in satisfaction of a larger sociopolitical goal. This is the opposite, mind you, of the more earnest Mary Tyler Moore Show and all its descendants, which are singularly interested in developing and showcasing believable comic personas, or characters. (Accordingly, if a good idea doesn’t work for an MTM lead, it’s not used. Here, it probably is used, regardless.) That said, in improving upon itself by intentionally undermining its premise, Maude is Norman Lear’s rule-breaker, for the rest of his hit ’70s sitcoms suffer when they’re forced to abandon their objectives and thus fail to achieve their own desired results in weekly story. Perhaps included in this latter category is Good Times, which premiered in the spring of 1974 after Esther Rolle spent nearly two years playing Florida Evans on Maude, with John Amos (then of Mary Tyler Moore) guest starring in three episodes as her husband Henry. As we’ll see, Good Times significantly tweaks the couple, renaming Amos’ character James, and moving them from New York to Chicago, but it’s basically the same Florida, which creates a legitimate association between the two shows. So, discussing Maude again in this rerun post, along with the other Norman Lear comedies that I’ve previously highlighted, has given me the chance to put them in context — pinpointing their strengths and weakness, especially as they pertain to character — while updating the record with my own thoughts on each classic and preparing us for Good Times, which perpetuates a lot of what we discussed. But that’s for later. In the meantime, I… well, I don’t have a list of episodes to share because it wasn’t worth revisiting the series in full for this preamble to Good Times. However, I will say that I screened all of the Maude episodes centered around Florida, and the best, by far, is Season One’s “Florida’s Problem,” which introduces Henry as her husband and leads to an expected “battle of the sexes” with the couples. As a primer for Good Times, and its two central characters, that’s the episode I most recommend watching!

Come back next week for the start of Good Times! And stay tuned tomorrow for a new Wildcard!